About Us

Vishwawalking explained

Ratings Explained

Ratings ExplainedVishwawalks

Parks, etc.

Funky Places

Future walks

Food

Gear and Health

Get Lost

Good reads

Links

Plants - Animals

Right to Ramble

Site map

Contact us

Vishwawalking

Preparing for a longer hikeBased on my hike of the Appalachian in the spring of 2013

From Horace Kephart's Camping

and Woodcraft, the MacMillan Company, 1944, p. 109:

From Horace Kephart's Camping

and Woodcraft, the MacMillan Company, 1944, p. 109:The problem of what to take on a trip resolves itself chiefly into a question of transportation... Beware of impediments that will be forever in the way and seldom or never used....

Be plain in the woods... We seek the woods to escape civilization for a time, and all that suggests it. There is a pleasure in achieving creditable results by the simplest means...

Let me not be misunderstood as counseling anybody to "rough it" by sleeping on the bare ground and eating nothing but hardtack and bacon. Only a tenderfoot will parade a scorn of comfort and a taste for useless hardships.

Can you do without it on the trail?

As 'Nessmuk' says: "We do not go into the woods to rough it; we go to smooth it—we get it rough enough in town. But let us live in simple natural life in the woods, and leave all frills behind."

An old campaigner is known by the simplicity of his equipment. He carries few "fixings," but every article has been well tested and it is the best that his purse can afford. He has learned by hard experience how steep are the mountain trails and how tangled the undergrowth and downwood in the primitive forest. He has learned too how to fashion on the spot 'boughten' things that we consider necessary at home.

The art of going "light but right" is hard to learn. I never knew a camper who did not burden himself, at first, with a lot of kickshaws that he did not need in the woods; nor one, if he learned anything, did not soon begin to weed them out; nor even a veteran who achieved his own ideal of lightness and serviceability...

Now it is not needful nor advisable for a camper in our time to suffer hardships from stinting his supplies. It is foolish to take insufficient bedding, or to rely on a diet of pork, beans and hardtack... The knack is in striking a happy medium between too much luggage and too little. Ideal outfitting is to have what we want, when we want it, and not to be bothered by anything else.

Kephart's words were written in 1917 and still hold. Keppler was a key person in the creation of the Appalachian Trail. His camping guide is now obviously dated with descriptions of the qualities of canvas, heavy kitchen gear, knives and guns, but his basic premises are as apt as ever and his writing makes for a lively read if you like such guides. I'll try to keep his advice in mind as I write.

There is a plethora of advice on the Internet regarding how to prepare for a longer hike. However, I was surprised that some of the items listed below were hard to find. Elevation and temperature are certainly discussed, but they are far less common a topic than, say, the ideal weight of a pack or what to carry in your pack.

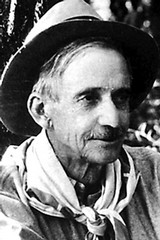

Horace Kephart.

Photo from scoutmastercg

Like most hikers, I have learned what not to carry from experience. How many times did I read something like, "The first time you hike, your pack will be too heavy." Yeah, yeah, I thought. That's the average person, not me. I've read Kephard. I know."

Wrong. I carry too much (still) and envy those who travel under the 10-kilogram (22 pounds) level FSI. (FSI = "From the Skin Out," meaning your total weight, including the clothes you are wearing.)

I'm still getting rid of "kickshaws" I don't need.

But to begin at the beginning. It is spring, moonless night... (Nice line, Mr. Thomas)

HYOH

Hike Your Own Hike. I first learned this acronym on the Appalachian from a hiker named Jeff.

It's important to develop your own routines and pace. If you constantly adapt to another's routines, you could find your body protesting in ways you have not anticipated.

I started the Appalachian solo and ended walking with four people who I expect will remain friends. Meeting new people was one of the most rewarding parts of my experience. We camped together, planned together, shared motel rooms and solved problems together. However, by day, we all travelled at our own pace, often meeting for lunch or taking a break together. Sometimes my pace matched another's and we walked together. Often I walked alone, knowing one of my mates was not that far ahead or behind me.

Rule #1: HYOH

Temperature

Check the average temperatures for the area you are hiking in. When I hiked the southern part of the Appalachian in late May and the first half of June, the temperature by day was between about 68 to 80 degrees F (20 to 26.5 degrees C). As so much of the Appalachian calculations are done in Farenheit and miles, those who rely on metric would do well to learn how to do rough conversions from imperial measures.

By night, the temperature could fall drastically. At the southern end of the trail on the night of May 24, temperatures dropped to the low 40sF (4.5C). Into June, there were still times when the night temperaturatures were in the 40s. These are the mountains, so temperatures can be 15 to 20 degrees F lower than the valleys (or "gaps" as they're called in the south). If the clouds move in, it can also get humid.

Meteoblue gives some good average stats for temperature, precipitation and more on Springer Mountain, for example. Nights average 8 degrees centigrade. Go Googling and be sure to note what weather is being calculated—gully or mountaintop.

I have no experience with this, but you can get snow on the higher sections of the southern trail until early April. South-north thru-hikers (most of whom start between January and April) have all kinds of dire tales of wonky weather at this time.

Rule #2: check and recheck weather conditions, both general and specific to the time you are hiking. Hike light, but carry enough so that you don't freeze!

Elevation

This is elementary my dear Watson, but I confess I neglected to seriously consider elevation on my southern Appalachian hike. This is a massive (and dumb) error.

I merrily calculated that my 60-something body could handily cover 20 miles a day. I was very wrong. My top day was something in excess of 16 miles. Generally it was about 12, with a few 8-mile days on hard sections and a couple of five or six-mile days when I wanted an early finish in a town, so I could have some down time.

Clingman's Dome in the Great Smokies at 6655 feet (2028.5 metres) is the highest point in the Appalachain Trail. From the south, the trail rises and drops, but mostly rises to this point.

On my first day on the southern Appalachian, I clambered up the 604 steps of the approach trail in Amicalola Falls State park followed by the Springer Mountain incline. I was thoroughly exhausted and wondered whether I could do the trail at this level of effort. Then I looked at my elevation map (in my guide by David Miller). The news was not good: while the steps are steep, Springer Mountain is not particularly so.

Here I am at the top of Springer Mountain after completing

the 8.8-mile approach trail. The exhilaration of getting to

the start of the trail is disguising my fatigue. Ahead lie

much more extreme elevations. May 24, 2013

Many of the mountains to come are much steeper. As I learned to pace myself, it got better, but I should have been better prepared on this one. Note to self: read the guide, look at the elevation graph, enjoy the written words, look at the elevation graph, check out shelter descriptions, look at the elevation graph.

Some downs are worse than ups. For example, much is made of going up Blood Mountain (from the south). I actually found it okay (steep, yes, but no huge deal). Going down was very steep, with some hairy parts.The only thing that keeps a hiker going here is the thought of Neel's Gap and a mattress in the bunkhouse.

Rule #3: check elevation graphs, then check them again. Estimate daily hikes based mostly on elevations rather than mileage.

Foot Care

Everyone has their own routine for caring for their feet—or they should have. If you don't, develop one fast. Long-distance hiking plays hell with your feet as they are subjected to constant pounding on earth and rock.

My routine: I sometimes wear two socks. A liner sock goes on first followed by a light smartwool sock. But before that, I put Band Aids (Limeys, read "plaster" here—which is what I still call them) on spots that look like they are getting rubbed excessively, even if they haven't yet become a blister. On tender spots, I also use either gel tubes or tubular foam for particular toes. I then powder my feet with Gold Bond foot powder..

The above is what I did back in 2013. I vary my foot routine. On the Camino in Spain, walking shoes and one set of medium hiking socks were enough. On the Appalachian today, I might still use the two-sock method. My daily walks in 2021 involve only one set of socks.

I carry an extra pair of socks (including the liner), which I will use if my first pair gets wet, sweaty or generally unbearable.

Don't wear cotton socks. Nylon and/or merino wool is best

Going up hills is kind on my feet even as I puff and wheeze on steep inclines. Going down, I use my walking poles extensively to protect my feet from excessive battering. My lungs like the downs; my feet don't.

The trend these days is on light hiking shoes/boots. I often still wear heavy leather hiking boots on Appalachian-style trails—the same ones in winter as in summer. They do provide maximum support, but I'll admit that it does add a lot of weight that my legs have to lift and drop thousands of times. The extra weight of each lift per step adds up to tons of extra weight. The rougher parts of the Appalachian warrants this for me, but I certainly will cut back to my "urban hikers" — a low cut, but still leather pair of walking shoes — on less arduous hikes.

I wear gaiters now. Dirty Girl Gaiters are light and efficient. They keep out mud splatters and stones and I feel they also protect me from tics.

Have a light but really comfortable pair of shoes/sandals for in camp. On of the joys of hiking is padding about in the evening in light shoes your feet can luxuriate in after your feet have expanded from the long walk.

You'll develop different pacing according to the terrain. Listen to what your feet (and indeed your whole body) are/is telling you and adjust accordingly. I stride on the flat and on the slight downhills, and even "scoot" as one fellow hiker dubbed my technique. Scooting is reserved for slight downhills with no rocks or tree roots. It involves slightly bending my knees and lifting my feet as little as possible while I "run" down the trail. Don't fear, I don't really run, but rather slither along the trail with my poles poised. The bent knees make it safer than a run and protect my feet from pounding the ground.

Downhills with steep or virtually vertical bits need careful positioning of your walking poles. My poles have saved me from many tumbles. People still do travel pole-less, but it's a rare walker that doesn't have at least one pole. I have two for balance. It definitely builds muscles in your arms and upper body, it takes a bit of stress off your feet and legs, and it's a safer walk. You can also use your poles as tent poles.

Rule #4: Pamper your feet as much as possible. They take a terrible beating, but you can make it tolerable. If you feel a blister coming on, stop immediately and deal with it!

Bears, snakes, mice poison ivy and other nasties

Much is made of the prevalence of bears in the Appalachians. They're black bears and so generally cut a wide berth around humans. Nevertheless care must be taken to keep them from stealing your food or from becoming accustomed to expecting food at campsites.

Many shelters on the Appalachian have bear cables, which make hanging your food really easy. If that is not possible, have the wherewithal to throw a rope over a branch to create your own bear hang. There are lots of videos online to show you how to do this. Here are a couple. These are instructions for a basic bear hang, although I'd go a few feet higher than these folks. And the water bottle as a weight? Not sure about that. I have a little lightweight bag that holds my bear hanging rope. I put a rock in the bag (some people advise against this as you might conk yourself on the head with your own rock.) Here's a bear hang technique I like. Hangs can get complicated; check out as many as you can to find a method you're comfortable with.

Snakes: I travelled with a person who had (and knew how to use) a venom kit — bonus! However, that is not necessary. Just take care. Tap a big log or root before you step over it—there may be a rattler snoozing on the other side. Keep an eye out on the trail for roots that magically turn into snakes. Again, snakes will take pains to avoid you, so it's nothing to get paranoid about but it is something to be aware of. Even when you're on your own and in deep "trail meditation" keep a third eye out for snakes.

This rattler was snoozing just off the trail, at the junction of the sidetrail

to the Sassafrass Gap Shelter in North Carolina, which is the first shelter

north of the Nantahala Outdoor Centre. June 7, 2013

Mice! Damn, these are a problem on the Appalachian. In shelters, even backpacks cleared of food can be chewed through by these persistent critters.

Some shelters have nails, some have nails with string and a plastic tin or bottle inverted part-way down the string to slow mice down. I slept in a Hennessey hammock on my 2013 trip. One night I found myself bashing mice that where using the rope that holds my fly netting above my head as a highway to get to higher points. They're wily. One sleeper had peanuts he'd forgotten in his pocket chewed. Apparently a mouse had entered his sleeping bag, crawled down to his pocket, had a feast and scampered off all while he was asleep. A bit creepy. Other campers have had mice crawl over their sleeping bags, faces and through their hair. One YouTube shows a hiker who claims he was bitten by a rat during sleep. Not sure about that one.

Some shelters are more mice free than others.

If you use a tent, it goes without saying that you must keep food out of it. However, I read one story of a hiker who was dismayed to find his tent chewed through by a mouse or other rodent looking for food. Sometimes all the care in the world cannot prevent such episodes; evasive action can reduce such incidents.

Chiggers: these are mites in the larvae stage. They attach to animals and feed off the fluids in skin cells. They don't burrow as many people think. One person I walked with got chiggers and they were very irritating; at night especially she was plagued by their itching. Chiggers develop into nymphs and adults, at which point they feed largely on plants.

One way to reduce the incidence of chiggers is to wear loose clothing. They like to lodge in places like under the waistband of underwear or socks, or in armpits. For more information read this piece.

Blackflies, mosquitoes and other bothersome flying insects: I found few of these on my spring Appalachian trip, although they were there. Some people are bothered more than others.

I carry a small piece of netting that I can drape over my hat if the biting insects get too aggressive. I seldom use it. I also walk wearing trousers (not shorts) to cut down on mosquito feeding grounds.

Poison

ivy:

it lines the Appalachian trail at points and its ivy wends its way

up

tree trunks. Be able to identify the three-leafed plant. There are

also

stinging nettles about, which are a minor nuisance. Check out this site created just for hikers.

Poison

ivy:

it lines the Appalachian trail at points and its ivy wends its way

up

tree trunks. Be able to identify the three-leafed plant. There are

also

stinging nettles about, which are a minor nuisance. Check out this site created just for hikers.One important note: alcohol-based cleansers should not be used to clean spots infected by poison ivy, because alcohols allows deeper penetration of the skin. However, early soap cleaning can avoid being plagued by poison ivy. Washing in water also helps.

I met many people who said they were not affected by poison ivy. The stats: Fifty per cent of us react to slight contact (!) and 20 per cent to more intense contact. Only 30 per cent have no reaction at all.

For a close-up of poison ivy, see the above sites, or here on my site.

An innocent part of the trail. But the little plants at the

bottom right (below the innocuous larger leaves) are

poison ivy. This is part of the Appalachian Trail north

of Wesser Bald, North Carolina. The more southern sections

of the trail in Georgia had much more of the plant lining the

trail. With positive identification and some care, poison ivy

can be avoided. June 6, 2013.

Ticks: These eight-legged creatures can carry nasty diseases like Lyme Disease. They drop on you from plants and burrow into your skin in search of blood. The best defence is to cover up: hat, long pants, etc. Also check from time to time in popular tick hideouts: groin, underarms, thighs, any warm comfy spot. Best removal technique is with tweezers (or even fingernails if you catch them in time). I carry a tick kit. Try to remove the entire tick and try not to squash it. You don't want to let any bits get left behind that could lead to the area getting infected. Disinfect the wound after removing the tick.

Rule #5: Be aware of what's out there. Be attentive. Be able to identify poison ivy. If you see a bear on the trail (and many do) give it as much space as possible—but don't run away.

Weight

This is a massive subject: what is essential, what can you do without, what's the lightest reasonable tent, sleeping bag, cooking stove, etc. etc. I'll deal with gear separately elsewhere. Regarding food, on the Appalachian, you can generally resupply every four or five days, so don't carry excessive amounts of food. I initially did, carrying close to 50 lbs (22.6 kg) of gear because I wanted to have my own dehydrated food, fruit leather, jerky, etc. Ouch! I soon dropped that to the low 30s (13.6 kg). I can do better.

By the way, regarding reading matter, many people object to ebooks. I agree they can make for a sterile read in comparison to paper books. However, on the trail, they're fantastic. My charged Kobo battery lasts for weeks of constant use and can be charged at a motel. In one light book, I carry 100 books. Luxury!

Read as much as you can online about pack weight and in books like The Complete Walker IV. It's dated, but if you click into the companies selling the latest gear, the basic information doesn't change much.

Rule #6: Carry only what you need. You may not need your favourite coffee mug, your favourite Buck knife, a GPS, three sets of extra batteries, or many other heavy items.

Return to main Appalachian Trail page

Page

created: June 26, 2013

Updated: September 7, 2021

Updated: September 7, 2021